Should the Longer Ending of Mark be in the Bible?

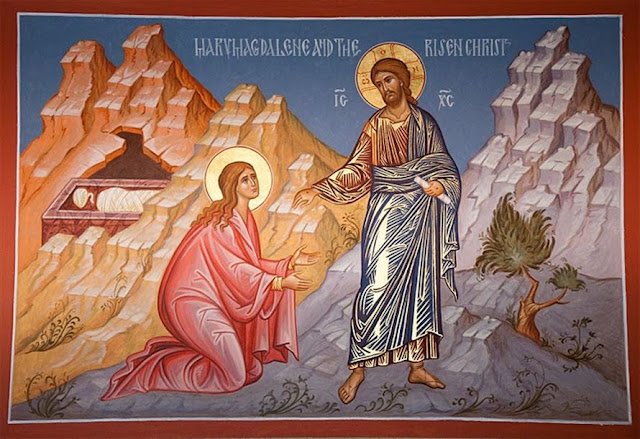

"Now when He rose early on the first day of the week, He appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom He had cast seven demons. She went and told those who had been with Him, as they mourned and wept. And when they heard that He was alive and had been seen by her, they did not believe. After that, He appeared in another form to two of them as they walked and went into the country. And they went and told it to the rest, but they did not believe them either. Later He appeared to the eleven as they sat at the table; and He rebuked their unbelief and hardness of heart, because they did not believe those who had seen Him after He had risen. And He said to them, 'Go into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature. He who believes and is baptized will be saved; but he who does not believe will be condemned. And these signs will follow those who believe: In My name they will cast out demons; they will speak with new tongues; they will take up serpents; and if they drink anything deadly, it will by no means hurt them; they will lay hands on the sick, and they will recover.' So then, after the Lord had spoken to them, He was received up into heaven, and sat down at the right hand of God. And they went out and preached everywhere, the Lord working with them and confirming the word through the accompanying signs. Amen."

1. The External Evidence Against Mark 16:9-20

The external evidence against Mark 16:9-20 is not as impressive as some Bible-footnotes and modern scholars make it seem. The number of Greek manuscripts in which the text stops at the end of 16:8 is two. The two Greek manuscripts are Codex Vaticanus (c. 325) and Codex Sinaiticus (c. 350), both of which Mark 16:8 is followed by nothing but the closing-title. They are the oldest two Greek manuscripts of Mark 16, but they are both younger than the testimony of St. Justin Martyr, Tatian, the unknown author of Epistula Apostolorum, and St. Irenaeus, from the second century—all of whom utilized the contents of Mark 16:9-20 in one way or another. These manuscripts are two heavyweight copies, but at the end of Mark, they both contain unusual features that lighten their usual weight. Codex Vaticanus (B) does not contain Mark 16:9-20, but following Mark 16:8 and preceding Luke 1:1, it contains a prolonged blank space, including an entire blank column. No other blank columns appear in the entire New Testament in this manuscript. The obvious answer to why it was left blank that the copyist was aware of copies that contained verses 9-20, and although he lacked these verses himself, he left space to give the eventual owner of the manuscript the option of including them. However, the blank space is not quite adequate to include verses 9-20. If one were to erase the closing-title and write the contents of verses 9-20, beginning at the end of verse 8, using the copyist’s normal handwriting, there would still be four lines of text yet to be written when one reached the end of the last line of the third column. It is for this reason that Daniel Wallace, referring to this blank space in his chapter of the 2008 book, Perspectives on the Ending of Mark, wrote: “The gap is clearly too small to allow for the LE.” However, his co-author J. K. Elliott stated less definitively: “Vaticanus actually contains a blank column after 16:8 that could possibly contain verses 9-20, suggesting that its scribe was aware of the existence of the longer reading.” If a copyist were to resort to compacted lettering—the script that the copyist of Sinaiticus used in the first six columns of the text of Luke—then the blank space is practically an exact fit. In a reconstruction of Mark 16:9-20 (second photo) in the blank space after 16:8, using cut-and-pasted characters from Mark 15:43-16:8, verse 20 concludes on the next-to-last line of the third column.

|

| The last page of Mark in Codex Vaticanus |

|

| The last page of Mark in Codex Vaticanus with verses 9-20 in the blank space after v. 8, using cut-and-pasted characters from Mark 15:43-16:8 on the same page |

In Codex Sinaiticus (N), the four pages that contain Mark 14:54-Luke 1:56 were not written by the same copyist who produced the surrounding pages. All four of these pages, including the page on which Mark ends, were made by someone else—probably the diorthotes, or proof-reader, before the pages were sewn together. The pages that had been made by the main copyist were removed, and new pages, beginning and ending at the same points, were added. Why? Almost certainly, the four replaced pages made by the main copyist did not contain Mark 16:9-20: each page of Mark in N has four columns; 16 columns on four pages would not have been enough to contain Mark 14:54-16:20 and Luke 1:1-56 in the copyist's normal handwriting, and he would have had no obvious reason to compress his lettering. Possibly the main copyist accidentally skipped from the end of Luke 1:4 to the beginning of Luke 1:8, omitting verses 5-7, and the supervisor decided that the best way to fix this mistake was to replace the entire four-page sheet.

|

| Columns 9, 10, 11, and 12 of the cancel-sheet in Codex Sinaiticus |

But we can't know for certain. What we can deduce, though, is very significant: the individual who made Sinaiticus' replacement-pages was one of the copyists who made Codex Vaticanus. The handwriting, the distinctive spelling, the ornamental decoration, and other features on the replacement-pages in N are remarkably similar to the same features in B. So the evidence from Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, while ancient and valuable, shows us only one narrow channel of the text's transmission, and in the case of the ending of Mark, their testimony represents one individual copyist who worked at Caesarea in the 300s. Furthermore, many ancient manuscripts contain the longer ending. They include Codex Washingtoniensis (c. 400), Codex Alexandrinus (c. 450), Codex Ephraemi (c. 450), and Codex Bezae (c. 400-500). These are just a few of the more than 1,500 manuscripts that include Mark 16:9-20. However, as mentioned above, the earliest manuscripts of Mark 16 are not the earliest evidence. There are several quotations of Mark 16:9-20 in St. Justin Martyr, Tatian, the unknown author of Epistula Apostolorum, and St. Irenaeus, all of which are younger than the earliest Greek manuscripts which include the longer ending.

The longer ending of Mark contains at least 14 different words that are not found anywhere else in the Gospel of Mark. Considering the fact that the Apostle Mark is ending his work on Jesus’ life and ministry, would it not be odd to start inserting new vocabulary in the last 12 verses of his work? This sounds damning until one notices that Mark uses 20 words in 15:40-16:4 (also 12 verses) that are also not found anywhere else in the Gospel of Mark. If the use of 14 new words in Mark 16:9-20 “points to the fact” that Mark didn’t write those verses, then the use of 20 new words in Mark 15:40-16:4 “points to the fact” that Mark didn’t write those 12 verses either. The truth is that in a relatively brief work such as the Gospel of Mark, every 12-verse segment is likely to have some unique vocabulary; if this argument was used more often, the entire Bible would be in question because unique authors used unique vocabulary. The vocabulary-based argument is a hollow shell that is only persuasive when used on listeners who are uninformed about the evidence.

3. Early Christian witnesses

Besides the four second-century writers already mentioned above—St. Justin Martyr, Tatian, the unknown author of Epistula Apostolorum, and St. Irenaeus—there are numerous early Church Fathers, early Christians, and anonymous documents that demonstrate not only their awareness but their acceptance of Mark 16:9-20. These individuals include the author of De rebaptismate (258), Eusebius of Caesarea (325), St. Aphrahat the Persian Sage (337), the unknown author of Acts of Pilate (300s), St. Ambrose of Milan (380s), St. Ephrem the Syrian (360s), Apostolic Constitutions (380), St. Augustine of Hippo (late 300s/early 400s), St. Jerome, Macarius Magnes, St. Prosper of Aquitaine, Marius Mercator, St. Marcus Eremita, St. Peter Chrysologus, Leontius of Jerusalem, and multiple Greek manuscripts mentioned by St. Augustine and St. Epiphanius of Salamis (late 300s).

4. Mark 16:9-20 is in accordance with the other Gospels

This argument is one of logic and consistency of scripture. It is really simple: nothing in the long ending of Mark contradicts the other gospels or the rest of the New Testament revelation. This consistency could, of course, be established through careful editing by a later author; however, the vast majority of people would utterly fail at such an attempt, so the likelihood of the content being created by someone other than the Apostle Mark and still maintaining this consistency is less than the simple likelihood that he wrote it himself. The passage is theologically sound and consistent with the rest of Scripture.

CONCLUSION

Although a scholarly consensus has developed in favor of the view that Mark 16:9-20 is not part of the original text of Mark, widespread errors about the longer ending by scholars are still spread around. It is claimed to be absent from "many of the oldest and most reliable manuscripts", it is said Mark ends at 16:8 "in many ancient Greek manuscripts", etc. Most Bible-footnotes about the passage are deceptively vague or outright false. I firmly believe that evidence supports the view that Mark 16:9-20 was in the Gospel of Mark in the form in which it was first transmitted for church-use. There is no question that at some point in the early history of copying and transcribing the text of Mark an issue arose regarding Mark 16:9-20 and its inclusion in the text. However, the passage is likely to have been attached in the production-stage than at a later stage. This is an issue of the original text’s transmission, not its inspiration. Mark 16:9-20 deserves its status as part of the canonical text and should be included in every edition of the New Testament.